Building Operations

Learn how to choose the right work order system for your facilities management team as spreadsheets and shared tools stop scaling

Jessica Wyman

Originally Published: May 23, 2020

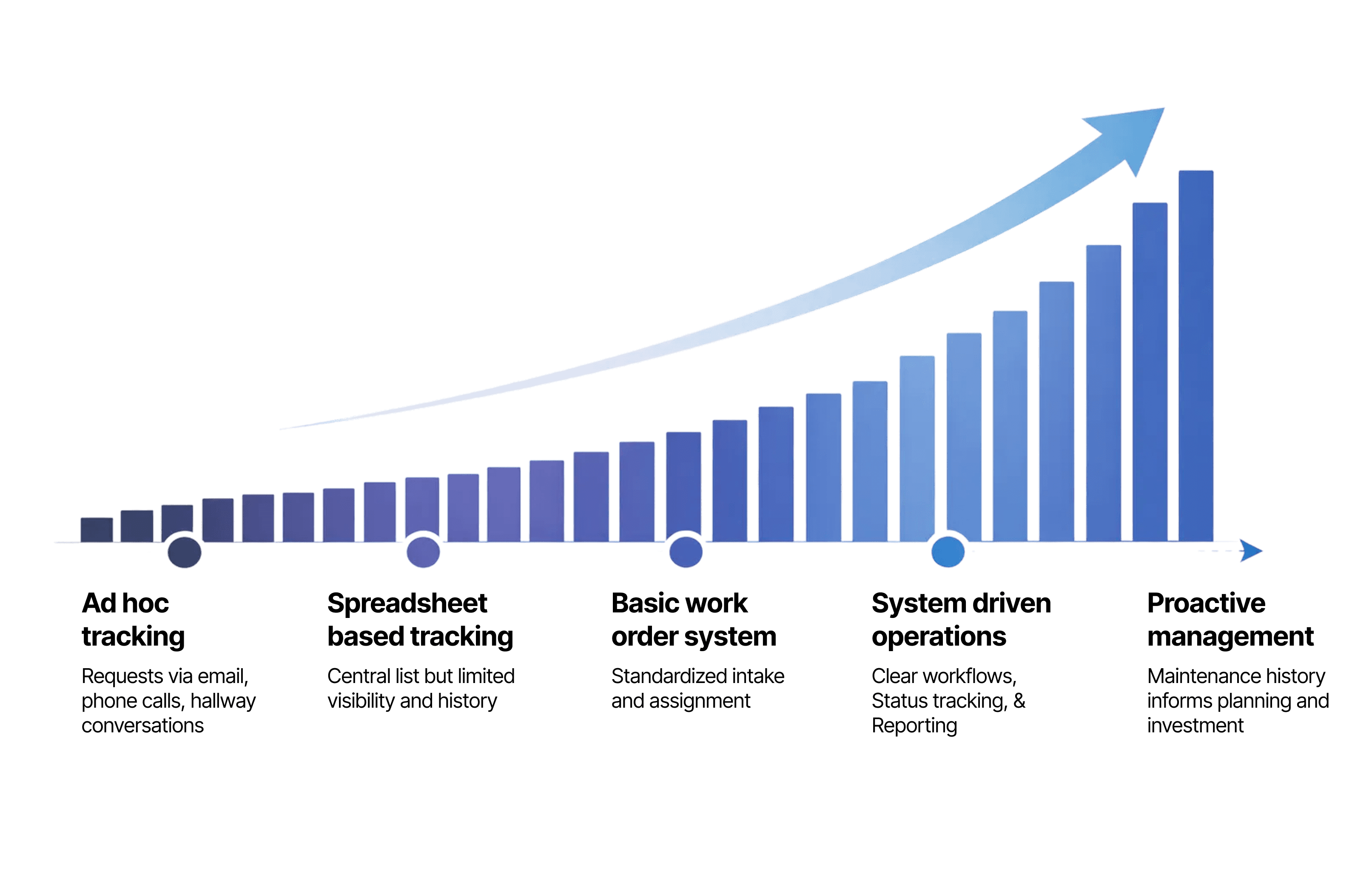

Many facilities management teams begin with simple tools to track maintenance work. Spreadsheets, shared folders, or basic ticket logs often work when the number of buildings, assets, and requests is small. As organizations grow, these tools struggle to keep up. Information becomes fragmented, handoffs increase, and more time is spent coordinating work than completing it.

This is typically the point where teams begin evaluating work order systems. The challenge is not identifying options, but choosing a system that supports how the team actually works today and how it will need to work as operations continue to scale. A poor fit can introduce new process overhead and slow teams down at the moment complexity increases.

This article explains how to choose a work order system using a structured, decision-first approach. The focus is on long-term fit, operational efficiency, and sustainability rather than feature lists or vendor claims.

Step 1: Define what success looks like before evaluating tools

Before evaluating work order systems, it is important to define what improvement actually means for your facilities management team. As operations scale, issues often surface as a general sense that work is harder to manage, but those issues need to be translated into clear, operational outcomes to guide decision making.

Success should be described in terms of how work is requested, prioritized, tracked, and reviewed, not in terms of software features. Defining this up front creates a shared reference point and ensures that systems are evaluated based on whether they improve daily operations rather than how they appear in a demo.

Example: Translating common pain points into success criteria

The table below illustrates how facilities teams commonly reframe operational pain points into clearer definitions of success as their operations grow. This example is meant to show the thinking process, not prescribe requirements.

Area of operation | Current state (as-is) | Desired outcome (what “success” looks like) | Why this matters when choosing a system |

|---|---|---|---|

Request intake | Requests arrive through multiple channels with inconsistent information | Requests arrive in a consistent format with required context | Systems should reduce follow-up work, not rely on manual clarification |

Prioritization | Work is prioritized informally or reactively | Work is prioritized consistently based on agreed criteria | Tools must support prioritization without constant oversight |

Response management | Response times vary depending on who submits the request | Response times are predictable and easier to manage | Systems should improve reliability, not just speed |

Backlog visibility | Open work is tracked manually or across tools | All open and pending work is visible in one place | Visibility becomes critical as volume increases |

Maintenance history | History is incomplete or difficult to access | Maintenance history is reliable and easy to review | Long-term decisions depend on accurate records |

Administrative effort | Significant time spent tracking and reconciling information | Minimal overhead required to manage work orders | Tools should reduce coordination effort |

Accountability | Ownership is unclear or changes informally | Responsibility is clearly defined at each stage | Systems should support clarity, not introduce ambiguity |

Once success is defined in operational terms, the next step is to apply this thinking to your own environment.

Step 2: Align internal stakeholders around the work order process

As facilities operations scale, work order systems begin to affect more than just the maintenance team. Requests are submitted by staff or occupants, reviewed and prioritized by supervisors, executed by technicians, and often reviewed by management or operations leadership. If these groups are not aligned on how the process should work, selecting new software will not resolve underlying friction.

Before evaluating systems, it is important to explicitly identify who is involved in the work order process and what each group needs from it. This helps prevent choosing a system that optimizes one part of the workflow while creating challenges elsewhere.

Mapping stakeholders in the work order process

Stakeholder group | Role in the process | What they need from the system | Risk if not considered |

|---|---|---|---|

Requesters | Submit maintenance issues | Simple intake and confirmation that requests were received | Low adoption or bypassing the system |

Facilities managers or supervisors | Review and prioritize work | Clear visibility into requests, priorities, and workload | Manual triage and inconsistent prioritization |

Technicians | Execute work orders | Clear scope, location, and access to relevant history | Rework, delays, or incomplete fixes |

Leadership or operations | Review performance and trends | Reliable reporting and historical insight | Decisions based on incomplete or misleading data |

IT or systems administrators | Support and maintain the system | Security, integrations, and manageable configuration | High support burden or stalled adoption |

Alignment at this stage reduces the risk of selecting a work order system that works well for one group while introducing friction for others.

Step 3: Document how work orders are handled today

Before comparing work order systems, it is important to clearly understand how work orders are handled today. Many teams underestimate how much process already exists or assume that software alone will fix issues that are actually procedural.

Documenting the current state helps separate process problems from tooling limitations. It also creates a baseline that can be used to evaluate whether a new system would meaningfully improve operations or simply digitize existing inefficiencies.

The goal of this step is not to design the future process, but to capture how work actually flows today, including where information is lost, delayed, or manually reconciled.

How to document your current work order process

The table below shows an example of how facilities teams document their current work order process. Use it as a reference, then adapt the structure to accurately reflect how work orders are handled in your own organization today.

Stage of the process | How it works today | Tools or channels used | Common issues or friction points |

|---|---|---|---|

Request submission | How maintenance issues are reported | Email, spreadsheets, shared folders, phone calls | Incomplete information, duplicate requests |

Intake and review | How requests are received and reviewed | Individual inboxes, shared lists | Requests missed or delayed |

Prioritization | How work is prioritized | Informal decisions, manual sorting | Inconsistent prioritization |

Assignment | How work is assigned to technicians | Verbal instructions, emails, spreadsheets | Lack of clarity or accountability |

Execution | How work is completed and documented | Paper notes, ad hoc updates | Work completed but not recorded |

Status tracking | How progress is tracked | Manual updates, separate trackers | Limited real-time visibility |

Completion and closeout | How work is marked complete | Informal confirmation, manual logs | Inaccurate or missing records |

History and reporting | How past work is reviewed | Spreadsheets, shared drives | Hard to analyze trends or repeat issues |

Capturing this information makes it easier to identify where existing tools no longer support the scale or complexity of operations and prepares the groundwork for evaluating potential improvements.

Step 4: Identify gaps between the current state and the desired state

Once the current work order process is documented and success criteria are defined, the next step is to compare the two. This comparison helps clarify where existing tools and processes no longer support how the team needs to operate as work volume and complexity increase.

Not all gaps point to a software problem. Some issues are procedural, such as unclear ownership or inconsistent intake. Others are structural, such as lack of shared visibility or unreliable maintenance history. Distinguishing between these types of gaps is critical. Choosing a system without this clarity often results in unnecessary complexity or tools that attempt to compensate for unresolved process issues.

The goal of this step is to identify which gaps genuinely require system support and which can be addressed through process changes.

Identifying gaps between current state and desired outcomes

The table below provides an example structure for comparing the current state documented in Step 3 with the success criteria defined in Step 1. Use this format to identify where gaps exist, what is causing them, and whether they should influence system selection.

Area of operation | Current state summary | Desired outcome | Gap identified | Primary cause |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Request intake | Requests arrive through multiple channels with missing context | Requests arrive consistently with required information | Incomplete and inconsistent intake | Process and tooling |

Prioritization | Work is prioritized manually and inconsistently | Work is prioritized using clear criteria | Unclear and reactive prioritization | Process |

Assignment | Assignments handled informally | Clear and traceable assignment | Lack of accountability | Process |

Status visibility | Progress tracked across separate tools | Real-time visibility into work status | Limited shared visibility | Tooling |

Maintenance history | Records incomplete or hard to access | Reliable, searchable history | Inability to analyze past work | Tooling |

Reporting | Reporting assembled manually | Consistent operational reporting | High administrative effort | Tooling and process |

Identifying the primary cause of each gap helps determine whether a work order system should address the issue directly or whether changes to the underlying process are required first. This distinction keeps system evaluations focused and prevents overcorrecting with unnecessary functionality.

Step 5: Separate mandatory requirements from nice to have features

Once gaps between the current state and desired outcomes are clear, the next step is to determine which capabilities a work order system must support and which are optional. One of the most common mistakes at this stage is treating every possible feature as essential, which often leads to tools that are difficult to configure, maintain, and adopt.

Mandatory requirements should be defined by the success criteria established earlier and the gaps identified in the previous step. These requirements represent the minimum capabilities a system must provide to improve daily operations. Features that sound appealing but do not directly address these needs should be treated as optional, even if they are commonly highlighted in vendor materials.

This distinction helps keep evaluations focused on operational impact rather than feature breadth.

Separating essential requirements from optional features

The table below provides an example structure for distinguishing between mandatory requirements and nice to have features. Use this format to document which capabilities are critical for your facilities management team and which can be deprioritized during system evaluation.

Capability area | Requirement description | Why it is mandatory or optional | Classification |

|---|---|---|---|

Request intake | Standardized submission with required information | Directly addresses inconsistent intake and missing context | Mandatory |

Prioritization | Ability to apply clear priority criteria | Supports predictable response management | Mandatory |

Assignment | Clear ownership and assignment tracking | Prevents work from being overlooked or duplicated | Mandatory |

Status tracking | Visibility into work order progress | Enables shared understanding of backlog and workload | Mandatory |

Maintenance history | Searchable record of past work | Supports troubleshooting and long-term planning | Mandatory |

Advanced reporting | Custom dashboards and analytics | Useful for analysis but not required for daily operations | Optional |

Deep customization | Extensive workflow customization options | Adds flexibility but increases setup and maintenance effort | Optional |

Integrations | Connections to other enterprise systems | Valuable in some environments but not always essential | Optional |

Clearly labeling requirements as mandatory or optional helps prevent feature-driven decision making and reduces the risk of selecting a system that introduces unnecessary complexity. This list can be refined further as systems are shortlisted, but establishing it early provides a strong filter for evaluation.

Step 6: Evaluate work order systems based on long-term operational fit

With mandatory requirements clearly defined, the next step is to evaluate work order systems based on how well they fit your facilities operations over time. At this stage, it is tempting to focus on demonstrations, feature breadth, or polished interfaces. While these elements can be useful, they rarely reveal how a system will perform under day-to-day operational conditions.

Long-term operational fit is about how a system supports real workflows as volume, complexity, and expectations increase. This includes how easily the system can be configured to match existing processes, how much effort is required to maintain it, and how well it adapts as needs change. A system that looks powerful but requires constant oversight can quickly become a burden for teams already managing growing workloads.

Evaluating systems through this lens helps avoid tools that solve short-term problems while introducing long-term overhead.

Evaluating systems for operational fit and sustainability

The table below provides an example structure for evaluating work order systems beyond feature checklists. Use this format to assess whether each option supports your mandatory requirements in a way that is sustainable for your facilities management team.

Evaluation area | Key question to ask | What to look for | Warning signs |

|---|---|---|---|

Workflow alignment | Does the system support how work orders actually flow today? | Configuration options that match existing processes | Heavy reliance on workarounds or customization |

Setup and configuration | How much effort is required to get the system usable? | Clear setup paths and manageable configuration | Long setup timelines or dependence on external support |

Ongoing administration | How much effort is needed to maintain the system? | Minimal ongoing management and clear ownership | Frequent adjustments or complex permissions |

Adoption likelihood | Will all stakeholder groups realistically use this system? | Simple interaction for requesters and technicians | Training-heavy workflows or resistance from users |

Scalability | Can the system handle increased volume and complexity? | Consistent performance as usage grows | Performance degradation or rigid structures |

Data quality over time | Will the system help maintain reliable records? | Structured data and clear status tracking | Inconsistent data entry or reliance on free text |

Change tolerance | Can the system adapt as processes evolve? | Flexible configuration without rework | Changes require significant reconfiguration |

Evaluating systems against these criteria helps ensure that short-listed options not only meet current needs but also remain usable as operations continue to evolve. This step reduces the risk of selecting a system that appears capable in isolation but becomes difficult to sustain in practice.

Step 7: Validate the system against real workflows before committing

Before making a final decision, shortlisted work order systems should be validated against real workflows, not idealized demonstrations. At this stage, the goal is to confirm that a system supports how work actually happens in your facilities operations, using your terminology, data, and constraints.

Validation should focus on everyday scenarios rather than edge cases or advanced features. This includes how requests are submitted, how information is presented to technicians, and how supervisors track progress across active work. Systems that appear capable in theory often reveal friction when tested against realistic conditions.

Testing systems this way helps reduce the risk of selecting a tool that looks effective during evaluation but fails to hold up once adopted.

Validating systems using realistic work order scenarios

The table below provides an example structure for validating shortlisted systems using real operational scenarios. Use this format to walk through common situations and capture where each system supports or hinders actual workflows.

Validation scenario | What to test | What good support looks like | Common friction points |

|---|---|---|---|

Submitting a request | Entering a typical maintenance request | Clear prompts and required context captured | Confusing fields or missing information |

Reviewing new requests | Assessing incoming work orders | Requests are easy to review and prioritize | Manual sorting or unclear priorities |

Assigning work | Assigning tasks to technicians | Ownership is clear and traceable | Ambiguous responsibility |

Executing work | Accessing information in the field | Technicians can quickly see scope and location | Switching between tools or missing details |

Updating status | Recording progress | Status updates are simple and consistent | Inconsistent or skipped updates |

Closing work orders | Completing and documenting work | Completion is clearly recorded | Incomplete records or extra steps |

Reviewing workload | Monitoring active and pending work | Clear visibility into backlog | Limited or delayed visibility |

Reviewing history | Looking up past work | History is easy to find and understand | Fragmented or unreliable records |

Validating systems against scenarios like these helps surface practical limitations early, before a decision is finalized. A system that performs well across everyday workflows is far more likely to succeed than one that only excels in curated demonstrations.

Making the final decision

Choosing a work order system is ultimately a decision about fit. Teams that take the time to define success, align stakeholders, and test systems against real workflows are far more likely to select tools that scale with operations rather than add friction. The goal is not to find the most feature-rich system, but to choose one that supports clarity, consistency, and adaptability as your facilities work continues to evolve.