Layer Workflow Guides

Layer Workflow Guides

Layer Workflow Guides

The Architect’s Guide to Construction Administration

The Architect’s Guide to Construction Administration

The Architect’s Guide to Construction Administration

Once a project begins construction, an architect is no longer designing the project. But the architect’s role isn't over yet! The architect must ensure that the final built building matches the design intent communicated in the architectural drawings and material selection package.

Pyline Tangsuvanich

Pyline Tangsuvanich

Pyline Tangsuvanich

Originally Published: Sep 25, 2024

Contents

Updated:Nov 19, 2025

First, what is Construction Administration?

In the building industry, construction administration is the final phase of the Architectural Design Process where several parties oversee the execution of a building project. It is the final phase of a project before tenants can occupy the building.

The design team does not construct the project - the general contractor does. This is why communication with the general contractor is crucial during this stage. The executed project should match the design depicted in the construction documents. The design team and the client must approve changes to the construction documents.

The primary parties involved in CA are architects, engineers, contractors, and clients.

The architect’s role includes site visits, to ensure quality and design intent; handling disputes; coordination; punch list resolution; reviewing payments; and conducting a final walk through.

Let’s dive into an overview of each of these responsibilities.

Preparing for Construction Administration

Construction administration services are outlined in the project contract. Prior to breaking ground, a kick-off meeting ensures across all parties. The general contractor or architect hosts this meeting. If the general contractor was not involved in the project from the beginning, this meeting allows them to familiarize themselves with the project requirements and project team.

Site Visits & Quality Control and Assurance

In traditional architect / client agreements, architects must advocate for the client’s best interest. One primary way architects do so is through site visits! The architect and other stakeholders, such as MEP engineers, conduct site visits to monitor the work during the building process. They occur at regular, scheduled intervals.

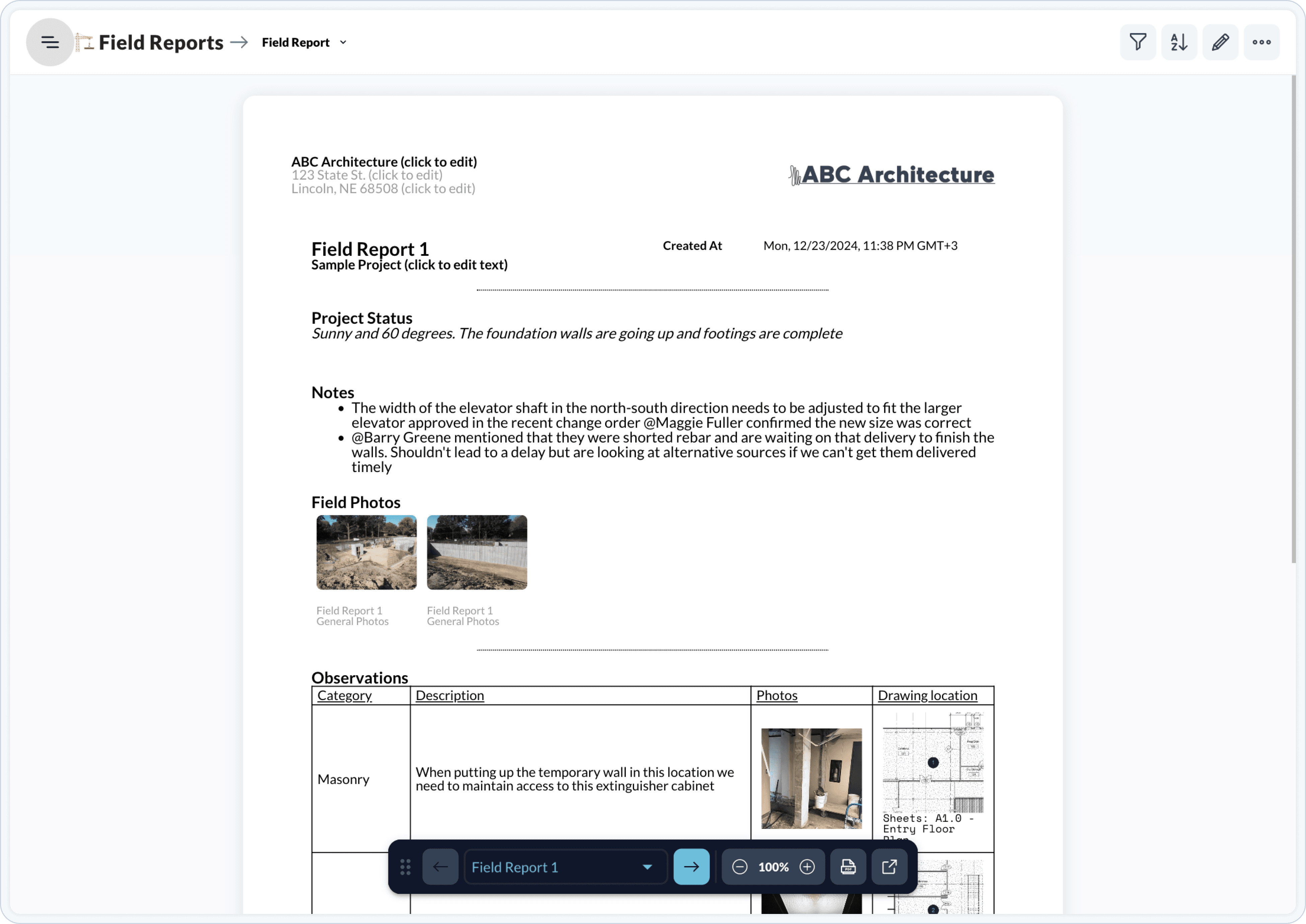

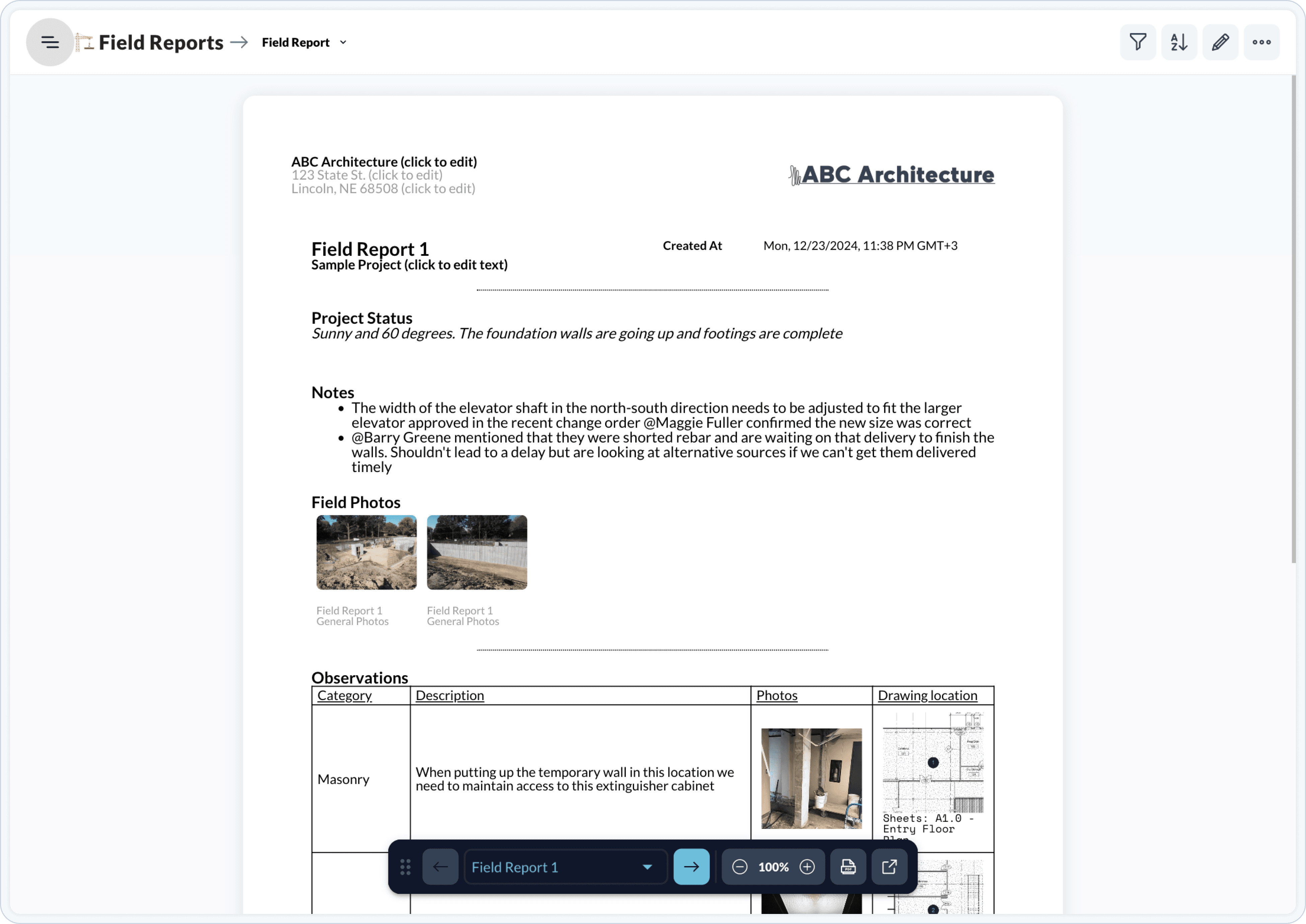

During site visits, architects look for things like non-conforming designs and any damages to materials. Architects capture progress through site photos, notes, and sketches. Often, they must prepare a report for the client that includes this information. That report is typically referred to as a field report.

Field reports aggregate the data gathered on site. Keep in mind that the entire project team is not always going on site. Therefore, field reports are useful documents to share with the client and relevant parties. Think of it like a snapshot of the project at that moment in time.

Communication with the Contractor

One of the most important features of successful project delivery is communication. Two formal means of communication during construction are requests for information (RFIs) and submittal packages. Contractors send both types to the design team for response and review.

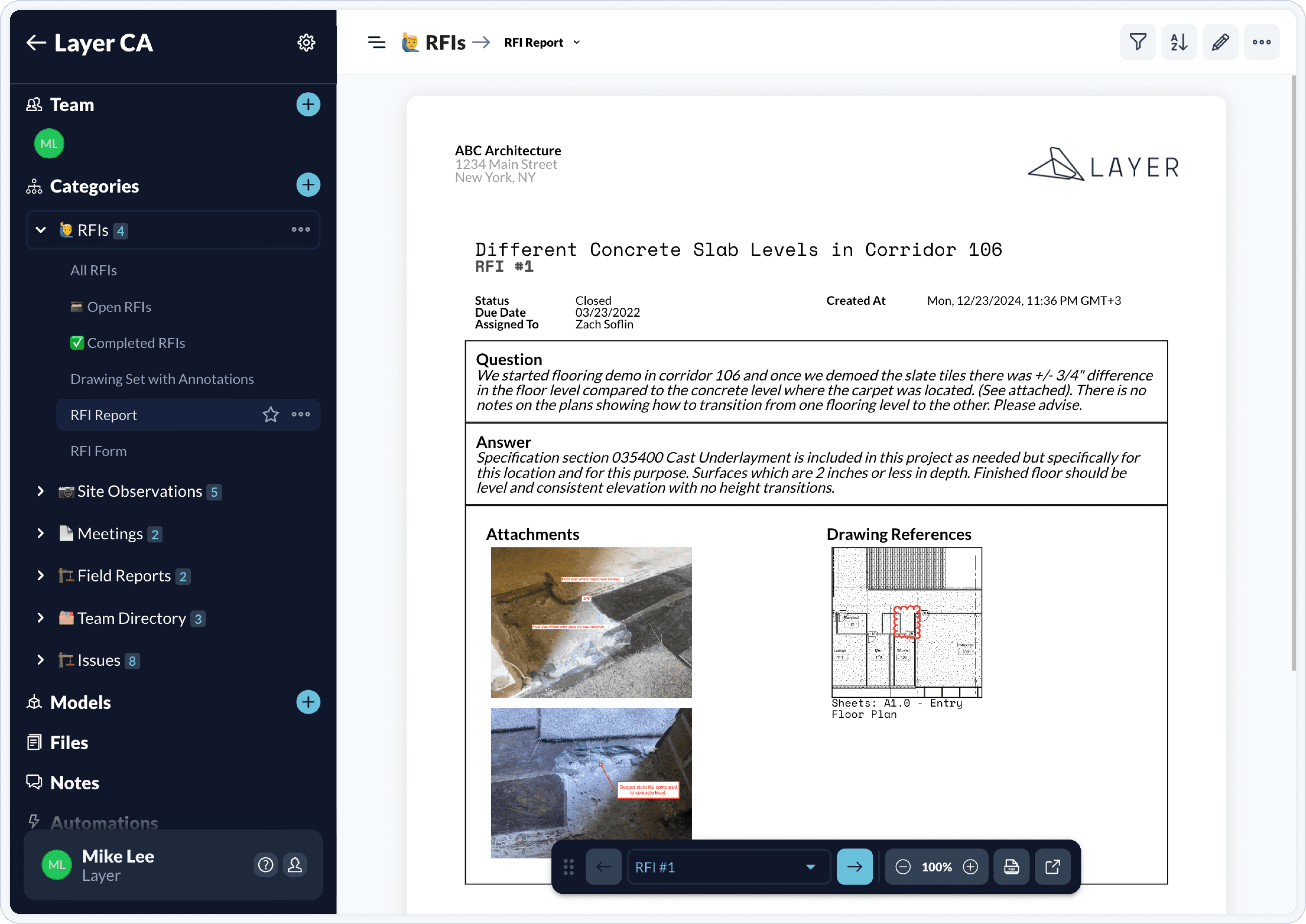

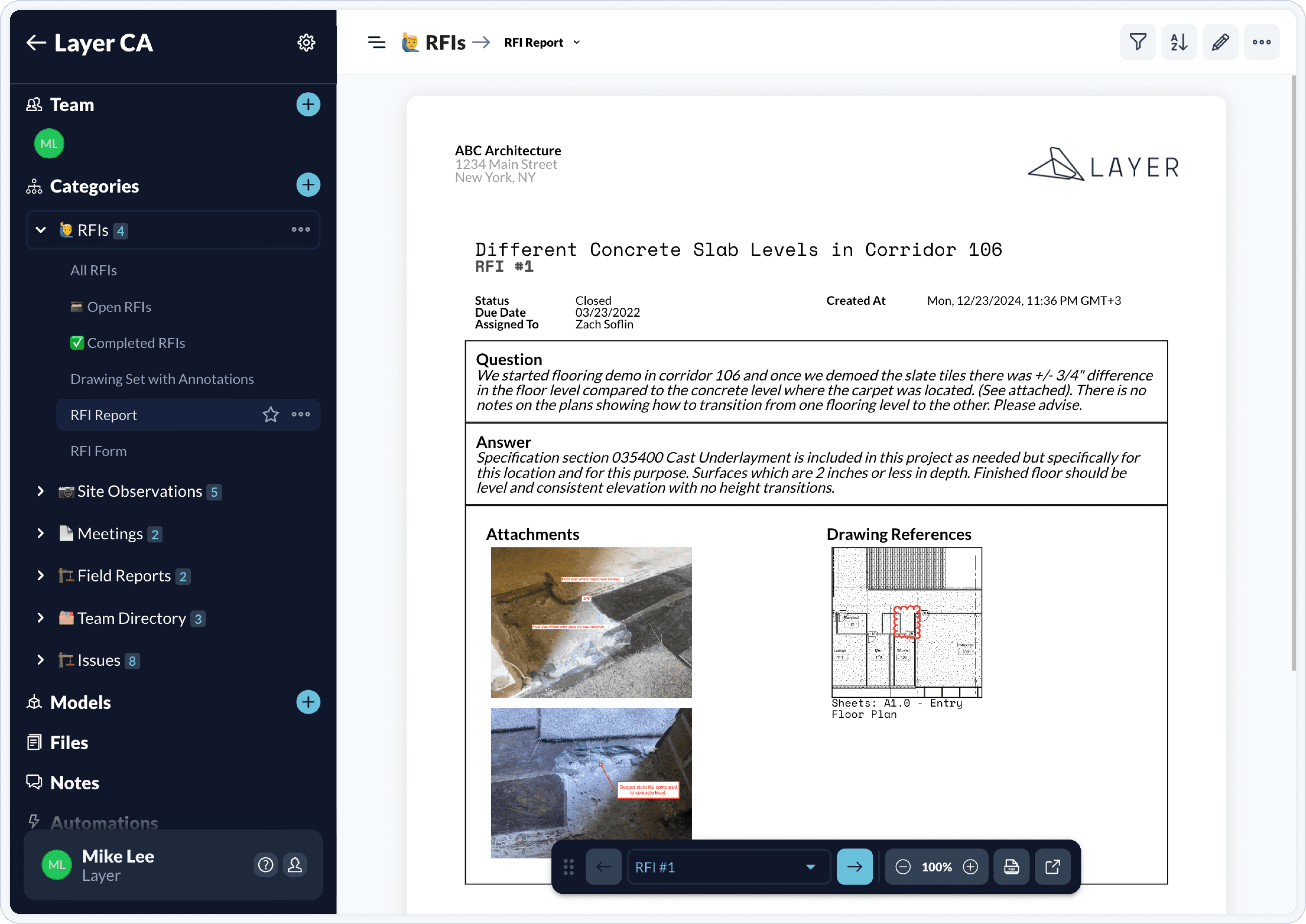

Drawings and specifications aren’t always 100% correct. There are ambiguities, gaps in information, or conflicts that the contractor discovers later on. RFIs are a means to provide clarity and keep the project moving. Contractors issue RFIs to the architect or engineer to provide more information before proceeding with work on site.

For instance, if the kitchen dimension on a floor plan conflicts with the dimension on the interior elevation drawing, the contractor won’t know which dimension to refer to. They’ll submit an RFI. The architect will resolve the discrepancy and provide a documented response to the contractor.

Construction projects may have hundreds of RFIs. Estimates show that the overhead cost of responding to a single RFI may be upwards of $1000. Aggregated across a large project, that is a huge inefficiency that many firms and GCs alike wish to reduce.

Due to the sheer number of RFIs, it's important to develop a method to streamline this process.

One way is to create a simple online form that the contractor’s project manager can use to submit an RFI. Architects should respond to the submission in a consistent and timely manner. Centralizing responses in a single source of truth ensures that all parties are on the same page about open items.

Submittals are not the same as RFIs

Submittals are documents that contain information for the design team to approve before items get fabricated and delivered to the project. Subcontractors issue submittals to general contractors. Submittals include material samples, cut sheets, and shop drawings. The design team’s responsibility is to review submittals for compliance with drawings. If the design team rejects and has mark-ups on the submittal, then the subcontractor must revise and resubmit for review.

Both RFIs and submittals are a means for the design team to clarify unknowns and confirm design intent before work continues.

Change Management

Changes to the contract documents happen. It’s rare that projects conform to the contract drawings and specifications. Project changes are addressed through change orders. Change orders don’t always come from general contractors. They can come from the client (e.g. requesting a different finish), unexpected job site conditions (e.g. a discovered pipe that needs removal), drawing errors and omissions (e.g. drawing did not depict enough clearance for a piece of equipment).

To initiate a change order, general contractors and their subs will prepare and submit them for the design team to review. Substantial changes to the initial design will impact budget and schedule. Architects must keep this in mind on behalf of the client’s expectations. Oftentimes, the contractors dip into the contingency budget to cover change orders, but that doesn’t alleviate the architect from assessing whether a change order is necessary.

Change orders can be a point of contention during construction. To avoid any conflict, transparency and open communication is paramount during the change order process. Often a General Contractor will have a dedicated Project Controls team for large project. As an architect, they are your ally in keeping things on track because their ultimate goal is to ensure the project sticks to the schedule.

→ Read more about the Project Controls Process

Payment and Documentation

Contractors get paid based on a schedule, not in one large lump sum. The combination of site visits, clear communication, and monitoring change orders all play into how a contractor gets paid.

Payments must be in line with the amount of work completed. The contractor wants to get paid as soon as possible, and the owner doesn’t want to pay more than they should. This is where the architect comes in. The architect’s role is to ensure the project is adhering to the proposed construction schedule. Change orders may amend the original schedule, which the architect should monitor.

It’s important for architects to complete payment reviews in a timely manner. Failure to pay contractors on time may result in a lien placed on the project, which will further delay completion.

Contractors will monitor payment progress on their end. Money in and money out is critical to how they pay their subs, suppliers, and themselves.

Project Closeout

As the project nears completion, there are a few critical pieces to accomplish before moving onto the next project. Now is not the time for owners and architects to make changes to the design, but to review for quality, conformance to documents, and completion.

A final site visit walkthrough sets the tone for project closeout. During this visit, all relevant parties thoroughly review the site conditions.

In most projects there are a few loose ends found during the final walkthrough

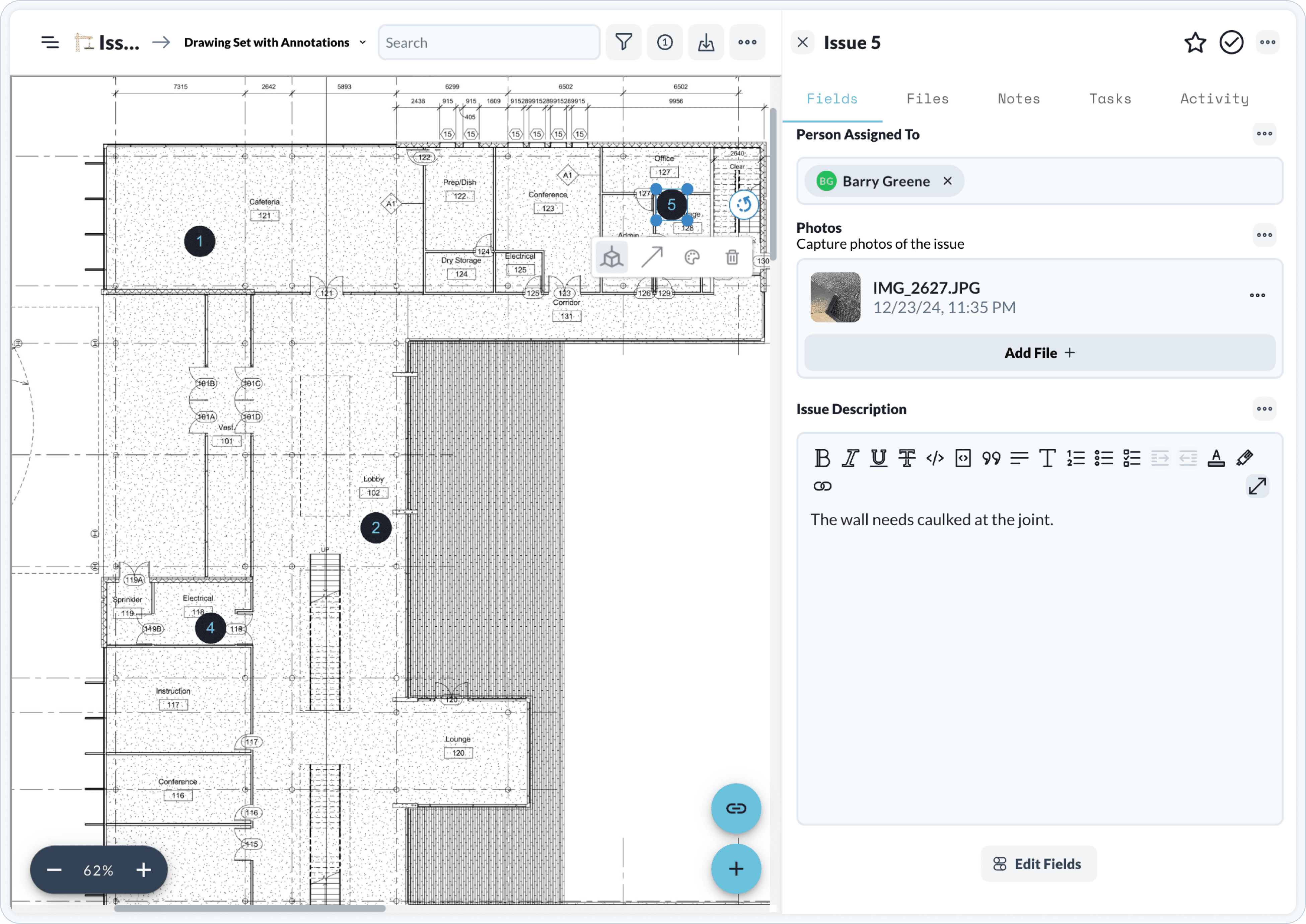

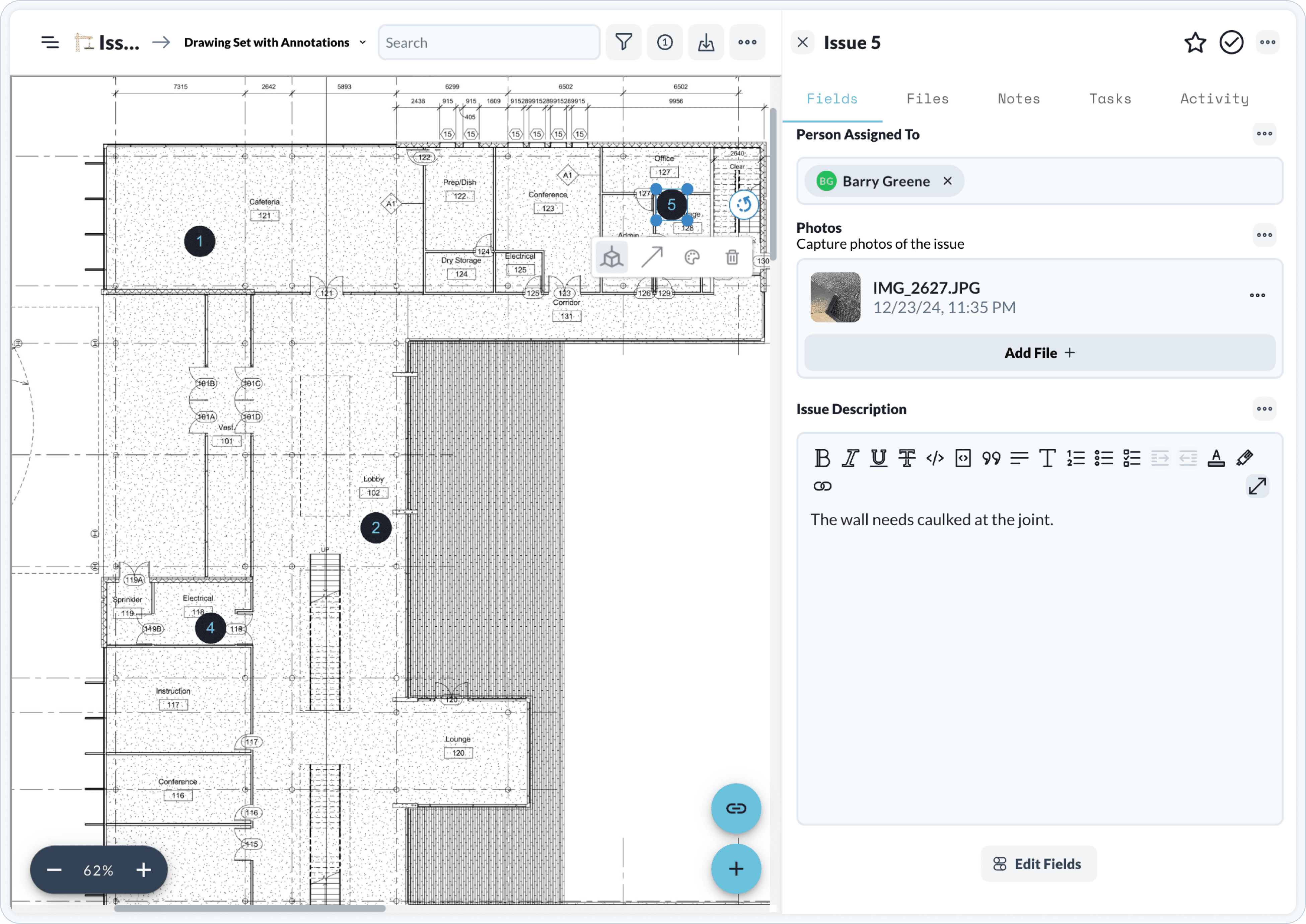

That’s where the punch list comes in. The design team documents areas that need attention and corrective action from the general contractor. The design team will snap photos and document issues they see on site. The general contractor must address the punch list items before receiving final payment.

After the general contractor completes punch list items, the building department conducts the final inspection. Upon approval, the building department issues a certificate of substantial completion and the building is ready for occupancy.

The last step before construction completion is project closeout and handover. Throughout the entire construction process, everyone has accumulated a mass amount of data. Data that lives in emails, texts, printed documents, and online drives. Oftentimes, the client contract stipulates what the design team must handover to the architect. Even if it doesn’t, it’s best practice to ensure the project is wrapped up for the client to ensure the project relationship ends in good standing.

Closeout documents include as-built drawings, approved change orders, BIM files, specification documents and warranties, and equipment operation manuals. As-builts aren’t always initially included in the architect’s scope of work. If they aren’t, then pairing the initial contract documents with approved change orders is sufficient for the client to understand the final built condition of the space.

Tidying up and assembling these documents in a single folder is a great way to package the data generated during the construction management process. A handover meeting is an opportunity to present the closeout documents and answer any final questions the client might have before the occupancy phase begins.

Post-Construction Phase

Usually, an architect’s work ends once after construction completion. Sometimes, the architect engages in additional services, such as post-occupancy evaluations and creating detailed as-builts.

There is no doubt that issues will arise upon building occupation. The client may reach out to the builder and design team to address certain issues that didn’t come up during construction. Issues may include material defects, incorrect installation, and malfunctioning equipment. Design teams should thoroughly address concerns that the client brings up.

This is rare for design teams to do, but gathering feedback from clients and tenants is beneficial. For example, if the door is awkwardly swinging into furniture or if there isn’t enough clearance for equipment, then the design team should know. This is information that the design team can take to the next project to ensure its occupants can reliably use a space.

A building comes to life once tenants move in

The space will start to deteriorate and change on Day 1.

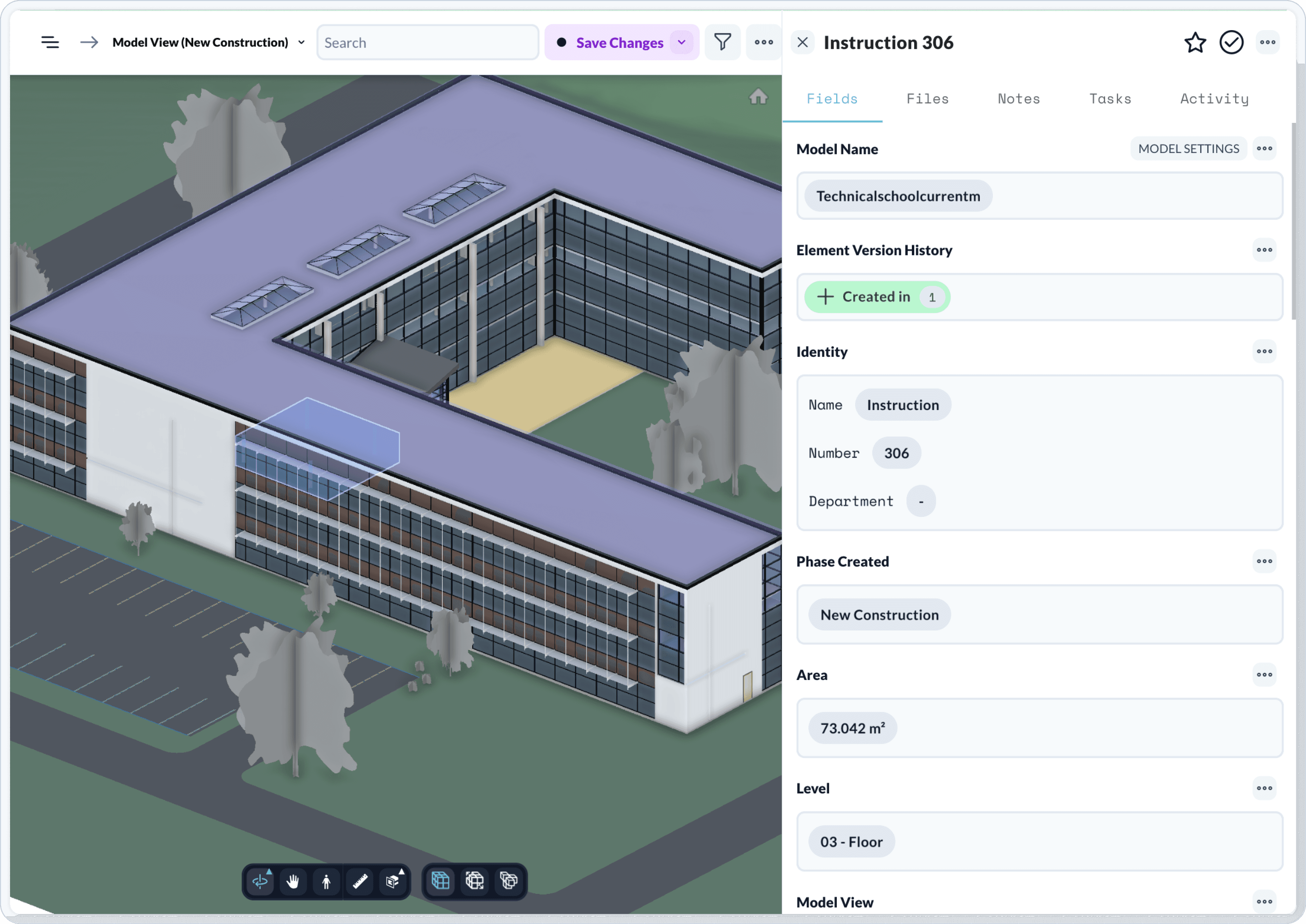

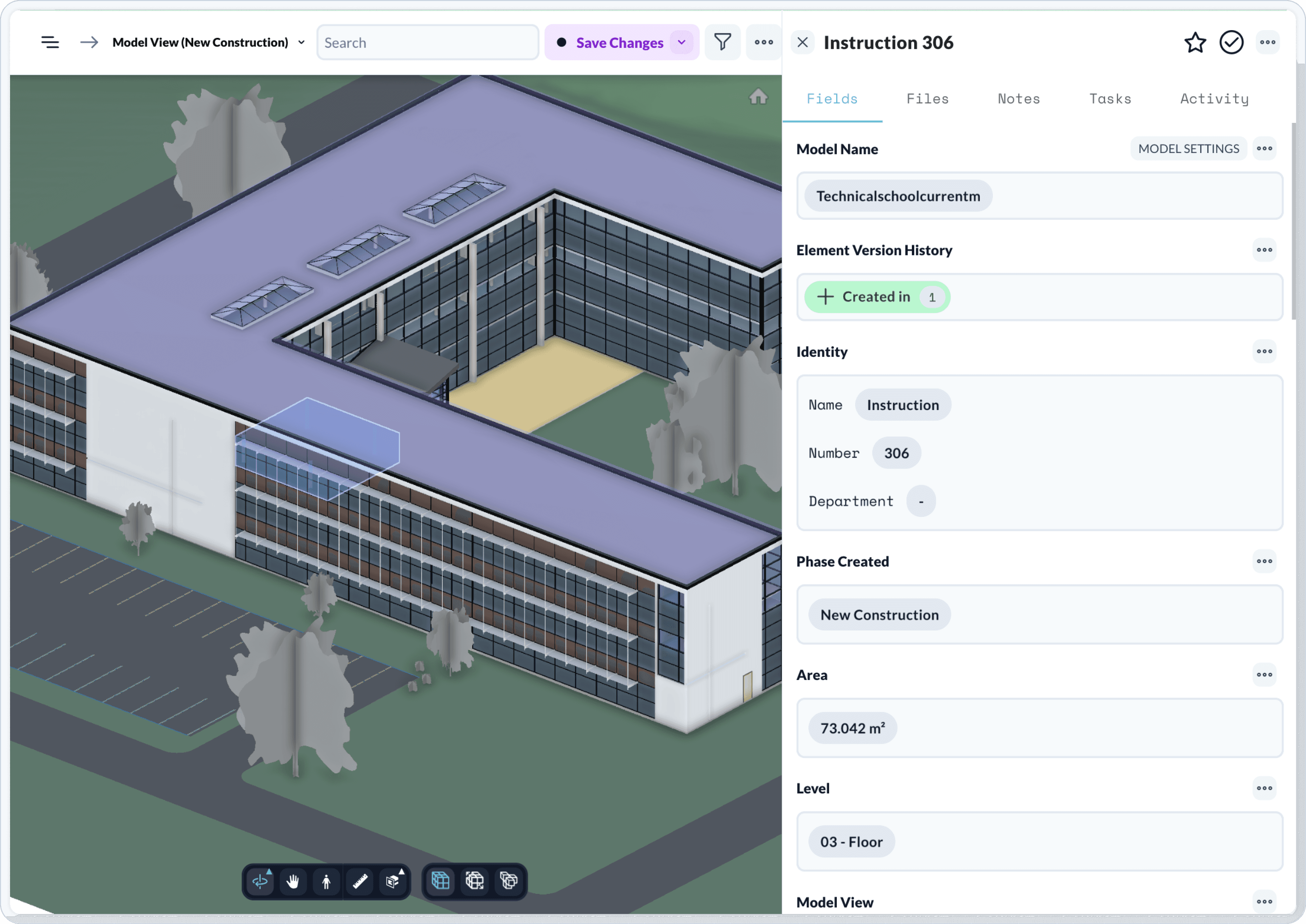

Architects can help clients leverage BIM files to plan and manage their spaces. By using a cloud-based viewer, clients don’t need to have special software installed to open BIM files. Having a birds eye view of the space will help the client with building operations and planning. Design teams can assist with ongoing services, like space planning.

Building long-term client relationships leads to repeat business, positive referrals for future projects, and enhances one’s reputation.

First, what is Construction Administration?

In the building industry, construction administration is the final phase of the Architectural Design Process where several parties oversee the execution of a building project. It is the final phase of a project before tenants can occupy the building.

The design team does not construct the project - the general contractor does. This is why communication with the general contractor is crucial during this stage. The executed project should match the design depicted in the construction documents. The design team and the client must approve changes to the construction documents.

The primary parties involved in CA are architects, engineers, contractors, and clients.

The architect’s role includes site visits, to ensure quality and design intent; handling disputes; coordination; punch list resolution; reviewing payments; and conducting a final walk through.

Let’s dive into an overview of each of these responsibilities.

Preparing for Construction Administration

Construction administration services are outlined in the project contract. Prior to breaking ground, a kick-off meeting ensures across all parties. The general contractor or architect hosts this meeting. If the general contractor was not involved in the project from the beginning, this meeting allows them to familiarize themselves with the project requirements and project team.

Site Visits & Quality Control and Assurance

In traditional architect / client agreements, architects must advocate for the client’s best interest. One primary way architects do so is through site visits! The architect and other stakeholders, such as MEP engineers, conduct site visits to monitor the work during the building process. They occur at regular, scheduled intervals.

During site visits, architects look for things like non-conforming designs and any damages to materials. Architects capture progress through site photos, notes, and sketches. Often, they must prepare a report for the client that includes this information. That report is typically referred to as a field report.

Field reports aggregate the data gathered on site. Keep in mind that the entire project team is not always going on site. Therefore, field reports are useful documents to share with the client and relevant parties. Think of it like a snapshot of the project at that moment in time.

Communication with the Contractor

One of the most important features of successful project delivery is communication. Two formal means of communication during construction are requests for information (RFIs) and submittal packages. Contractors send both types to the design team for response and review.

Drawings and specifications aren’t always 100% correct. There are ambiguities, gaps in information, or conflicts that the contractor discovers later on. RFIs are a means to provide clarity and keep the project moving. Contractors issue RFIs to the architect or engineer to provide more information before proceeding with work on site.

For instance, if the kitchen dimension on a floor plan conflicts with the dimension on the interior elevation drawing, the contractor won’t know which dimension to refer to. They’ll submit an RFI. The architect will resolve the discrepancy and provide a documented response to the contractor.

Construction projects may have hundreds of RFIs. Estimates show that the overhead cost of responding to a single RFI may be upwards of $1000. Aggregated across a large project, that is a huge inefficiency that many firms and GCs alike wish to reduce.

Due to the sheer number of RFIs, it's important to develop a method to streamline this process.

One way is to create a simple online form that the contractor’s project manager can use to submit an RFI. Architects should respond to the submission in a consistent and timely manner. Centralizing responses in a single source of truth ensures that all parties are on the same page about open items.

Submittals are not the same as RFIs

Submittals are documents that contain information for the design team to approve before items get fabricated and delivered to the project. Subcontractors issue submittals to general contractors. Submittals include material samples, cut sheets, and shop drawings. The design team’s responsibility is to review submittals for compliance with drawings. If the design team rejects and has mark-ups on the submittal, then the subcontractor must revise and resubmit for review.

Both RFIs and submittals are a means for the design team to clarify unknowns and confirm design intent before work continues.

Change Management

Changes to the contract documents happen. It’s rare that projects conform to the contract drawings and specifications. Project changes are addressed through change orders. Change orders don’t always come from general contractors. They can come from the client (e.g. requesting a different finish), unexpected job site conditions (e.g. a discovered pipe that needs removal), drawing errors and omissions (e.g. drawing did not depict enough clearance for a piece of equipment).

To initiate a change order, general contractors and their subs will prepare and submit them for the design team to review. Substantial changes to the initial design will impact budget and schedule. Architects must keep this in mind on behalf of the client’s expectations. Oftentimes, the contractors dip into the contingency budget to cover change orders, but that doesn’t alleviate the architect from assessing whether a change order is necessary.

Change orders can be a point of contention during construction. To avoid any conflict, transparency and open communication is paramount during the change order process. Often a General Contractor will have a dedicated Project Controls team for large project. As an architect, they are your ally in keeping things on track because their ultimate goal is to ensure the project sticks to the schedule.

→ Read more about the Project Controls Process

Payment and Documentation

Contractors get paid based on a schedule, not in one large lump sum. The combination of site visits, clear communication, and monitoring change orders all play into how a contractor gets paid.

Payments must be in line with the amount of work completed. The contractor wants to get paid as soon as possible, and the owner doesn’t want to pay more than they should. This is where the architect comes in. The architect’s role is to ensure the project is adhering to the proposed construction schedule. Change orders may amend the original schedule, which the architect should monitor.

It’s important for architects to complete payment reviews in a timely manner. Failure to pay contractors on time may result in a lien placed on the project, which will further delay completion.

Contractors will monitor payment progress on their end. Money in and money out is critical to how they pay their subs, suppliers, and themselves.

Project Closeout

As the project nears completion, there are a few critical pieces to accomplish before moving onto the next project. Now is not the time for owners and architects to make changes to the design, but to review for quality, conformance to documents, and completion.

A final site visit walkthrough sets the tone for project closeout. During this visit, all relevant parties thoroughly review the site conditions.

In most projects there are a few loose ends found during the final walkthrough

That’s where the punch list comes in. The design team documents areas that need attention and corrective action from the general contractor. The design team will snap photos and document issues they see on site. The general contractor must address the punch list items before receiving final payment.

After the general contractor completes punch list items, the building department conducts the final inspection. Upon approval, the building department issues a certificate of substantial completion and the building is ready for occupancy.

The last step before construction completion is project closeout and handover. Throughout the entire construction process, everyone has accumulated a mass amount of data. Data that lives in emails, texts, printed documents, and online drives. Oftentimes, the client contract stipulates what the design team must handover to the architect. Even if it doesn’t, it’s best practice to ensure the project is wrapped up for the client to ensure the project relationship ends in good standing.

Closeout documents include as-built drawings, approved change orders, BIM files, specification documents and warranties, and equipment operation manuals. As-builts aren’t always initially included in the architect’s scope of work. If they aren’t, then pairing the initial contract documents with approved change orders is sufficient for the client to understand the final built condition of the space.

Tidying up and assembling these documents in a single folder is a great way to package the data generated during the construction management process. A handover meeting is an opportunity to present the closeout documents and answer any final questions the client might have before the occupancy phase begins.

Post-Construction Phase

Usually, an architect’s work ends once after construction completion. Sometimes, the architect engages in additional services, such as post-occupancy evaluations and creating detailed as-builts.

There is no doubt that issues will arise upon building occupation. The client may reach out to the builder and design team to address certain issues that didn’t come up during construction. Issues may include material defects, incorrect installation, and malfunctioning equipment. Design teams should thoroughly address concerns that the client brings up.

This is rare for design teams to do, but gathering feedback from clients and tenants is beneficial. For example, if the door is awkwardly swinging into furniture or if there isn’t enough clearance for equipment, then the design team should know. This is information that the design team can take to the next project to ensure its occupants can reliably use a space.

A building comes to life once tenants move in

The space will start to deteriorate and change on Day 1.

Architects can help clients leverage BIM files to plan and manage their spaces. By using a cloud-based viewer, clients don’t need to have special software installed to open BIM files. Having a birds eye view of the space will help the client with building operations and planning. Design teams can assist with ongoing services, like space planning.

Building long-term client relationships leads to repeat business, positive referrals for future projects, and enhances one’s reputation.

Get Started Today

Want to see how Layer can transform the way your team works?

Get Started Today

Want to see how Layer can transform the way your team works?

Get Started Today

Want to see how Layer can transform the way your team works?

Solutions

Solutions

Solutions